Normally drones develop from unfertilized eggs and are haploid. Diploid drones (called also "biparental males") develop from fertilized eggs The chromosome number as proof that drones can arise from fertilized eggs of the honeybee,

, Volume 5, p.149–154, (1966)

[1]The presence of spermatozoa in eggs as proof that drones can develop from inseminated eggs of the honeybee,

, Volume 5, p.71–78, (1966)

[2] which are homozygous at sex locus. In nature diploid drones do not survive until the end of larval development. The larvae of diploid drones are eaten by workers What happens to diploid drone larvae in a honeybee colony,

, Volume 2, p.73-75, (1963)

[3] within few hours after hatching from egg The hatchability of "lethal" eggs in a two sex allele fraternity of honeybees,

, Volume 1, p.6-13, (1962)

[4] despite the fact that they are viable Rearing and viability of diploid drone larvae,

, Volume 2, Number 2, p.77–84, (1963)

[5]Study on the comparative viability of diploid and haploid larval drone honeybees,

, Volume 4, p.12–16, (1965)

[6].

Adult (imago) diploid drones can be reared in laboratory by hatching eggs in incubator and feeding larvae with royal jelly without workers A method of rearing diploid drones in a honeybee colony,

, Volume 8, p.65-74, (1969)

[7]Rearing diploid drones on royal jelly or bee milk,

, Volume 8, p.169-173, (1969)

[8]. The larva can be transferred to colony after 2-3 days. At this age workers feed them normally. Diploid drones can be reared also in autumn in mating nuclei with about 1000 workers A new, simple method for rearing diploid drones in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.),

, Volume 31, Number 4, p.525–530, (2000)

[9].

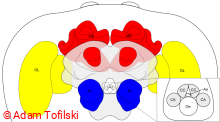

Externally adult diploid drones are similar to haploid drones. In comparison to haploid drones diploid once are larger, heavier Comparative biometrical investigation on diploid drones of the honeybee. I. The head,

, Volume 16, p.131–142, (1977)

[10]Comparative biometrical investigation on diploid drones of the honeybee. II. The thorax,

, Volume 17, p.195–205, (1978)

[11]Comparative biometrical investigation on diploid drones of the honeybee. III. The abdomen and weight,

, Volume 17, p.206–217, (1978)

[12] but see Sex determination in Bees. II. Additivity of maleness genes in Apis mellifera,

, Volume 79, p.213-217, (1975)

[13]Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

[14], have smaller testes Genic balance, heterozygosity and inheritance of testis size in diploid drone honeybees,

, Volume 13, p.77–85, (1974)

[15]Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

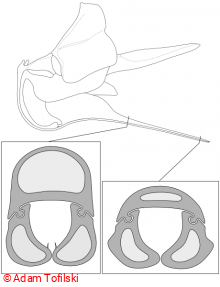

[14], fewer testicular tubules Reproductive organs of haploid and diploid drone honeybees,

, Volume 12, p.35-51, (1973)

[16], fewer wing hooks Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

[14] and lower vitellogenin concentration Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

[14]. Diploid drone larvae produce more cuticular hydrocarbons than workers but less than haploid drones Cannibalism of diploid drone larvae in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) is released by odd pattern of cuticular substances,

, Volume 43, Number 2, p.69–74, (2004)

[17] but see Ursache von Kannibalismus bei Arbeiterinnen der Honigbiene (Apis mellifera L.) an diploider Drohnenbrut,

, Volume 87, p.30, (1994)

[18].

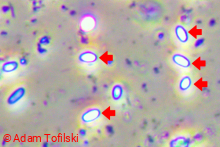

Diploid drones produce diploid spermatozoa Spermatogenesis in diploid drones of the honeybee,

, Volume 13, Number 3, p.183–190, (1974)

[19] containing twice as much DNA as haploid spermatozoa DNA content of spermatids and spermatozoa of haploid and diploid drone honeybees,

, Volume 14, p.3–8, (1975)

[20]Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

[14]. Diploid spermatozoa are longer than haploid spermatozoa; their head is particularly long Lengths of haploid and diploid spermatozoa of the honeybee and the question of the production of triploid workers,

, Volume 22, p.146-149, (1983)

[21]. Ultrastructure of haploid and diploid drones is similar Ultrastructure of single and multiple diploid honeybee spermatozoa,

, Volume 23, Number 3, p.123–135, (1984)

[22]. In theory triploid honey bees can be obtained by inseminating queen with diploid spermatozoa Lengths of haploid and diploid spermatozoa of the honeybee and the question of the production of triploid workers,

, Volume 22, p.146-149, (1983)

[21], however, this was not achieved so far because of small number of sperm produced by diploid drones.

Workers recognize the diploid drones larvae using substances present at their bodies Diploid drone substance–cannibalism substance,

, Maryland, p.471–472, (1967)

[23]. It was suggested that diploid drones produce pheromone called "cannibalism substance" which is a signal to workers that they should be destroyed Diploid drone substance–cannibalism substance,

, Maryland, p.471–472, (1967)

[23] see also Studies on the ‘cannibalism substance’ of diploid drone honey bee larvae,

, Volume 10, p.314-315, (1975)

[24]. Such self-destructive behaviour of diploid drones can evolve because they are neither able to reproduce nor help their relatives. Eating of the diploid drones at early stage of larval development allows to save valuable resources and produce bigger number of their relatives. However, no cuticular compound specific for diploid drone larvae was found Cannibalism of diploid drone larvae in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) is released by odd pattern of cuticular substances,

, Volume 43, Number 2, p.69–74, (2004)

[17]. First instar larvae of haploid and diploid drones differ in relative amount of cuticular compounds Cannibalism of diploid drone larvae in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) is released by odd pattern of cuticular substances,

, Volume 43, Number 2, p.69–74, (2004)

[17] and the difference can be used by workers for detection of diploid drones. In older larvae the differences in cuticular compounds are smaller Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones,

, Volume 4, Number 4, p.624-641, (2005)

[14].

In natural conditions frequency of diploid drones (before destruction by workers) in a colony is 0.05±0.03 (mean±SD) Estimation of the number of sex alleles and queen matings from diploid male frequencies in a population of Apis mellifera,

, Volume 86, p.583-596, (1977)

[25]. The frequency can be much higher in case of inbreeding. In colonies with large proportion of diploid drones there is "shot brood" - brood of different ages scattered irregularly on a comb Viability and sex determination in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.),

, Volume 36, p.500-509, (1951)

[26]Estimation of the number of lethal alleles in a panmitic population of Apis mellifera L.,

, Volume 41, p.179-188, (1956)

[27]Occurrence of lethal eggs in the honeybee,

, Volume 14, p.123–130, (1958)

[28]Exploitation of comb cells for brood rearing in honeybee colonies with larvae of different survival rates,

, Volume 15, p.123-135, (1984)

[29]. Multiple mating by the queen leads to reduced variance of proportion of diploid drones present in the colony The evolution of polyandry by queens in social Hymenoptera: the significance of the timing of removal of diploid males,

, Volume 26, p.343-348, (1990)

[30]. When a queen is artificially inseminated with semen of one drone which is her brother, half of her female offspring develop into diploid drones Viability and sex determination in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.),

, Volume 36, p.500-509, (1951)

[26].

Reviews: The story of diploid drones in the honeybee,

, Volume 5, p.151-154, (1974)

[31]Sex determination,

, Orlando, p.91-119, (1986)

[32]

Other references: Origin of unusual bees [in Polish],

, Volume 6, Issue 2, Number 2, p.49-63, (1963)

[33]Drones from fertilized eggs and biology of sex determination in the honeybee,

, Volume 9, Issue 5, Number 5, p.251-254, (1963)

[34]Drone larvae from fertilized eggs of the honeybee,

, Volume 2, Number 1, p.19–24, (1963)

[35]Genetic proof of the origin of drones from fertilized eggs of the honeybee,

, Volume 4, Number 1, p.7–11, (1965)

[36]Do honeybees eat diploid drone larvae because they are in worker cells?,

, Volume 4, p.65–70, (1965)

[37]Rearing diploid drone larvae in queen cells in a colony,

, Volume 4, p.143–148, (1965)

[38]Genetic background of sexuality in the diploid drone honeybee.,

, Volume 19, Number 2, p.89–95, (1980)

[39]The biparental origin of adult honeybee drones proved by mutant genes,

, Volume 11, p.41–49, (1972)

[40]Laranja: a new honey bee mutation. Gene dosage and maleness of diploid drones,

, Volume 64, Number 4, p.227-230, (1973)

[41]Changes in tissue polyploidization during development of worker, queen, haploid and diploid drone honeybees,

, Volume 24, Number 4, p.214–224, (1985)

[42]

- Log in to post comments

- Log in to post comments